BLOGブログ

Understanding Attitudes About Success and Innovation in Japanese Business

(和訳は下に続く)

Automobiles don’t just come about as

the result of a single engineer’s hobby.

What we have created was born of

painstaking research and knowledge accumulated

in various fields by many people,

and of efforts and numerous failures

spanning long years.

— Kiichiro Toyoda, Nov 1936

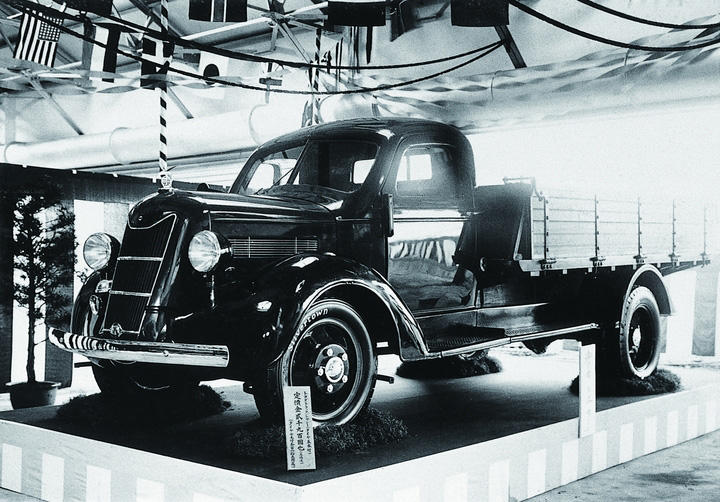

…The first vehicle sold by Toyota was the Model G1 truck, which was plagued by continuous breakdowns. Whenever Kiichiro learned that a G1 had broken down, he rushed to the scene, got under the vehicle to determine the problem and apologized to the customer. In this action, which occurred numerous times, we can see the origins at Toyota of “Customer First” and “Quality First”, which continue to this very day. Of equal importance is for us to never forget those customers in our first days who purchased such vehicles and used them while enduring great inconvenience.

— Toyota Corporate Website

Can Japan make success in the innovative environment?

Recently, I had an interesting conversation with a foreign employee of a Japanese company. He was frustrated at what he said was a lack of innovation in the Japanese business mindset and claimed that Japan’s global success would suffer unless its business culture changed drastically and learned to innovate quickly. He had explained his point to his Japanese managers and colleagues and was unhappy with the lack of change in their attitude. I often hear this from foreign workers here: “Why are they so slow?” “They should do it our way” “Innovation requires radical change” “Why are there so many rules?” and other similar sentiments. What makes people new to Japan’s business world so insistent that Japanese are doing things incorrectly?

Analysis using Hofstede’s model

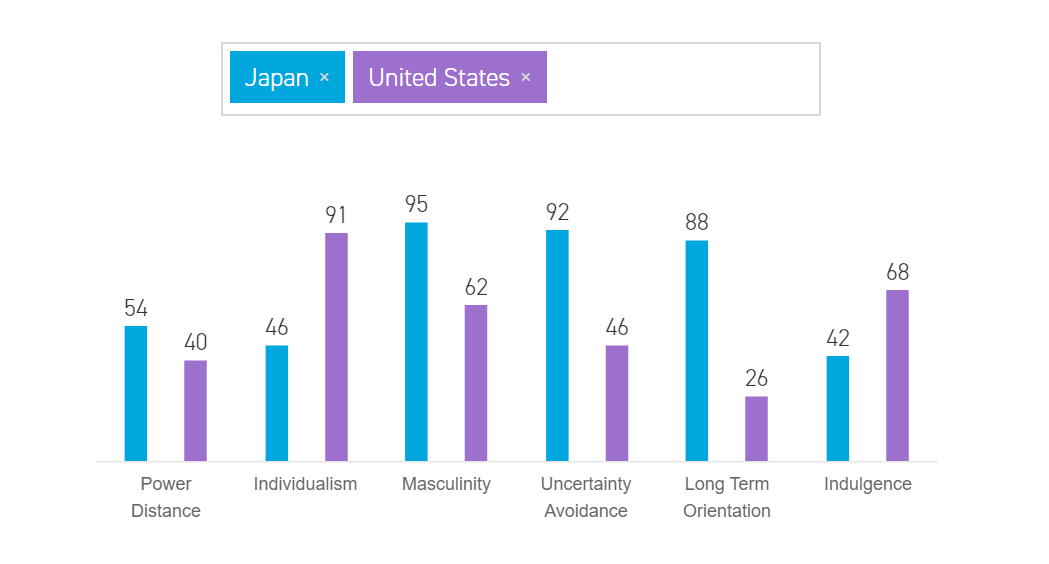

Professor Geert Hofstede tells us that culture is the collective programming of the human mind with which one group distinguishes itself from another. He highlights that discussions about culture are only relevant when done in comparison with other cultures. Hofstede’s 6-D Model provides us with a framework to compare cultural values and in doing so we come to understand how one national culture (like Japan) can define success differently from another culture (like my friend’s home country). While many factors contribute to a company’s success Hofstede’s dimensions can help us understand the role of national culture in defining success through the values that are most important in a country.

Within the 6-D Model, Japan scores high in the areas that emphasize:

- motivation for success as a group,

- a long-term view of results and planning

- a high need for structure and rules to ensure safety and continuity, and

- a tendency to suppress individual goals over group needs

In comparison, people in my friend’s home country value:

- individual motivations for success,

- emphasize shorter-term results and quicker turn-arounds for goals and milestones, and

- a more risk-taking and trial and error attitude towards achieving results

Unique Japanese strengths

The Toyota quotes above remind me of some Japanese terms. Kaizen helped me understand that in Japan there is no end to improvement: it is an ongoing, iterative process that can last years. Genba tells us that in Japan successful businesses require a ‘boots on the ground’ familiarity with how things are done, which includes not only the factory floor worker but the manager, and a functional knowledge of what your customer needs. Keys to success in a Japanese worldview come from continuous improvement, over long periods of time, by experts and on-site, hands-on management. Toyota is known worldwide for its innovation in manufacturing processes and as a real-world example of these attributes in action. Also check the zippers on your clothes — they’re likely made by YKK, a Japanese company that has had a dominant world market share since the 80’s. Zippers and cars weren’t invented in Japan, but they were definitely improved upon here.

Group craftsmanship

I suggested to my friend that he consider the concept of group craftsmanship as how Japan viewed its path towards innovation and success. The concepts of genba, and kaizen, among others, exemplify this. When we think of “craftsmanship” we think of something carefully planned and executed; an almost artistic endeavor. A discipline that requires patience and exacting attention to detail. Skilled work. Something that takes time. These are all quintessential Japanese cultural values.

A few years ago, I found a list of the world’s oldest businesses, companies that have been in constant operation since their inception. Of the twenty oldest businesses, nine are Japanese, including the oldest company in the world. In fact, of all the companies that are 200 years or older, over 3000 are Japanese. A 2017 article in the Japanese Nikkei newspaper referenced Toyota’s ten to twenty-year plan of building up their business. Panasonic’s founder Matsushita Konosuke, in the 1932, outlined a 250-year plan as their roadmap to success. When we process these facts, it shouldn’t surprise us that within Hofstede’s 6-D Model, Japan scores as having one of the more pronounced long-term perspectives on time among cultures around the world.

Success is culturally relative

There is no one right path to success, and innovation can be found in a number of ways. The key, of course, is context — what works best for your employees, your management, your market, your situation. But also important is having functional knowledge of how cultures compare. Knowing how Japan scores within Hofstede’s 6-D Model tells us what success and innovation might look like here: a long-term perspectives and value group craftsmanship through incremental improvements has a significant impact on what success and innovation looks like here. Knowing also that your own cultural view on success is not necessarily going to match how that concept is seen in Japan.

Talking about culture is hard, but inevitable in today’s diverse workplace. When we do have these discussions, we often use imprecise terminology and rely on our own subjective experience rather than objective data-based analysis. Hofstede’s 6-D Model gives us a framework with which we can start having better discussions and data-informed comparisons. In doing so, the 6-D Model can help us avoid misunderstandings on relative concepts like success and move us toward more productive discussions in the workplace.

Resources for this article:

Geert Hofstede website – http://geerthofstede.com

Hofstede Insights – http://hofstede-insights.com

Hofstede Insights Japan – http://hofstede.jp

Toyota company history – https://www.toyota-global.com/company/history_of_toyota/75years/message/index.html

Oldest companies article – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_oldest_companies

Special thanks to Erika Visser, Yuriko Miyazaki, Chika Miyamori and especially MaryAnne Jorgensen for sharing with me their keen insight and advice.

Andrew Robinson has lived and worked in Japan for over 28 years in the areas of business training and information technology. These experiences, as well as his academic background (in history, psychology, sociology and anthropology) have all helped him appreciate the insights that Hofstede’s research provides for understanding business in Japan.

(和訳)

日本のビジネスにおける成功と革新についての態度を理解する

自動車は、何もないところから現れたわけではありません。

1人のエンジニアの趣味の結果です。

私たちが創造したものは

さまざまな分野の多くの人々の骨の折れる研究と知識の蓄積

そして努力と多くの失敗のから生まれました

– 豊田喜一郎、1936年11月

…トヨタが最初に販売した車両はG1型トラックで、継続的な故障に悩まされていました。喜一郎は、G1型トラックが故障したことを知ったときはいつでも現場に駆けつけ、問題を突き止めるために車の下に入り、顧客に謝罪してました。トヨタの「顧客第一」と「品質第一」の起源は何度も発生したこの行動の中から生まれ、今日でも続いています。同じように重要なのは、このような車を購入し多大な不便に耐えながら使用しくださった最初の日の顧客を、決して忘れないことです。

– Toyota Corporate Website

革新していくことを学ばない限り、日本のグローバルな成功は難しい?

最近、私は日本企業に勤める外国人社員と面白い会話を持ちました。彼は、日本人にはイノベーションというマインドが欠けているとイライラし、その文化が劇的に変わってスピーディに革新していくことを学ばない限り、日本のグローバルな成功は難しいだろうと言うのです。彼は、日本人の上司や同僚にそのような考えを伝えても、彼らの態度が変わる様子もないと不満そうでした。「なんでこんなにゆっくりなのか?」「我々のようにするべきだ」「変革とは劇的な変化を要するものだ」「なんで、そんなにルールが多い??」というようなことは、日本で働く外国人から本当によく聞く話です。日本のビジネス社会にやってきた外国人たちは、なぜこんなにも、日本のやり方はおかしいと思うのでしょうか?

6次元モデルにおける日本

ヘールト・ホフステード教授は、文化とは、「あるグループを他のグループから区別する心のプログラミング」と言っています。ホフステード教授は、文化の議論は、他の文化と比較のうえでのみ意味があると強調します。ホフステードの6次元モデルは、国民文化が持つ価値観を比較して見るフレームワークを提供してくれます。ある国の文化(例えば日本)にとって「成功とは何を意味するか」が、他の文化(例えば、私の友人の国)とは異なると理解できるようになるのです。もちろん、企業の成功には多様な要因が関係します。そして、ホフステードの次元は、その国において重要な価値観が成功の定義にも影響を与えているとういことを教えてくれます。

6次元モデルにおいて、日本は次のような領域で高いスコアとなっています。

- 集団として成功したいという気持ち

- 長期の時間軸で成果や計画を考えること

- 安全性や継続性を担保するために仕組みや規則を欲する強い気持ち

- 集団の目的のために個人の目的をおさえる傾向

比較して、私の友人の母国の価値観は、

- 個人として成功したいという気持ち

- 短期の時間軸で成果を考え、ゴールやマイルストーンを短く設定したいこと

- 成果を上げるためには、リスクを取ってトライ&エラーがよいと考える傾向

日本の強み

冒頭に上げたトヨタ自動車の引用を見て、私は日本語から生まれたいくつかの用語を思い出しました。“Kaizen“という言葉で、私は、日本では改良することに終わりがないのだと知りました。それは常に継続していて、何年もの間も繰り返し続くこともあるのです。”Genba”という言葉は、日本でビジネスに成功するためには、現地に足を運び、何が起こっているのか理解することが必要だと教えてくれます。生産現場の職員だけではなく、管理の立場にある人々も同様です。顧客が望んでいることに実体験から得られる知識をもって答えていく、ということが成功に結びつくのです。日本という国の世界観では、成功の鍵は、長い年月において、専門性の高い人々と実務にも関わっていく管理職と共に、たゆまなく向上し続けるということにあるのです。トヨタの製造プロセスの技術革新は世界的に知られていますが、まさにお手本と言えます。ところで、あなたの洋服のファスナーをチェックしてみてください― おそらくYKKが作ったものではないでしょうか?1980年代からの圧倒的な世界市場シェアを誇っている日本の企業が作っています。ファスナーも車も日本で発明されたものではありません。でも、この日本という国において改良されてきたのです。

集団で職人技

私は、私の友人に、日本の革新と成功について、 “group craftsmanship(集団で職人技)”と考えてみるように勧めました。”Genba”や“Kaizen“というような考え方は、そういうことだと思うのです。craftsmanship(職人技)というと、私は、何か注意深く計画をたて実施していく…ほとんど芸術的と言っていいような献身的な努力を感じます。根気強さや細部にまで気を配る規律観。熟練の仕事。時間がかかるけれど何か特別なもの。これらは日本がもっている典型的な文化の価値観なのです。

数年前、私は世界で最も古いビジネス、創業以来ずっと操業されている企業のリストを見つけました。世界で最も古い企業は日本企業で、上位20位のうち9社が日本企業です。また、200年以上続いている企業というリストにも、日本の企業が3000社以上も入っています。日本経済新聞の2017年の記事には、トヨタ自動車の10年から20年先に及ぶ長期計画が紹介されていました。1932年に、パナソニックの創業者である松下幸之助は、成功へのロードマップとして250年先を見据えた計画を語りました。このような事実を知って驚いてはいけません。なぜなら、ホフステードの6次元モデルによると、日本は、世界の中でも顕著な「長期志向」のスコアをもっていることが示されているのです。

この国における成功や革新

成功に向けて、一つの正しい方法というものはありません。そして、革新とはいろいろな方法から見つかるものです。重要なのは、もちろん文脈や背景です。あなた方の従業員、管理職、市場、おかれている状況に、どのような方法がベストなのかということです。そして、加えて重要なのは、文化を相対的に考えるスキルです。ホフステードの6次元モデルにおいて、日本のスコアがどの様になっているのかを知ると、日本が成功や革新についてどのように見ているかがわかります。長期的志向で、集団で職人的にたゆまない改良を続けていく事を大切にする価値観。この価値観は、この国における成功や革新に対する考え方に大きな影響があるとわかります。そして、自分自身の成功や革新に対する価値観が、日本でも同じであるとは限らないということを理解することを教えてくれるのです。

文化について話すことは難しいですが、今日の多様な職場では避けられないことです。私たちは、文化について話をする際、客観データからの分析というよりも、用語を曖昧に使ったり個人的な経験談に頼ったりしがちです。ホフステードの6次元モデルはより良い議論を導き、データによる比較を可能にしてくれるフレームワークです。この6次元モデルは、「成功」というような相対的な概念について誤解を防ぎ、ビジネスにおいて実り多い議論となることを助けてくれるのです。

この記事のリソース

Geert Hofstedeウェブサイト – http://geerthofstede.com

Hofstede Insights – http://hofstede-insights.com

ホフステード・インサイツ・ジャパン – http://hofstede.jp

トヨタ自動車の会社沿革 – https://www.toyota-global.com/company/history_of_toyota/75years/message/index.html

最も古い企業の記事 – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_oldest_companies

Erika Visser、Miyazaki Yuriko、Chika Miyamori、そして特にMaryAnne Jorgensenからの洞察とアドバイスに心から感謝します。

Andrew Robinsonは、日本でビジネストレーニングと情報技術の分野で仕事をして28年になる。この長年の経験とアカデミックな経歴(歴史、心理学、社会学、文化人類学)から、ホフステード博士の深い洞察に共感し、日本におけるビジネスの理解に博士の理論に助けられている。

Andrew Robinson

ファシリテーター

In the twenty-eight years Andrew Robinson has lived in Japan, he has worked in various areas — academics, business-executive training, teaching project management courses and most recently in information technology. In almost all cases, this work was with multicultural teams and in culturally diverse environments. At university in the United States, his dual majors were in Western Literature and History, with minors in Psychology, Sociology and Anthropology. Over his career in Japan he has worked in a variety of business environments, ranging from large multinational corporations to small start-ups.

In addition to being certified as an Associate Partner by Hofstede Insights, Andrew has received training in other human capital methodologies like Lumina Learning, Human Synergistics and Organization and Relationship Systems Coaching (ORSC), as well as IT-related certifications in various cloud systems, DevOps, Agile workflow design and for Google and Apple systems administration.